Differentiating Truth, Knowledge and Belief

When something's too big, too vague, inaccessible, or always changing, we rely on beliefs to sketch in the knowledge we’re missing. But is it truth?

In What is Truth, we introduced a recipe for knowing truth. We used the example of a chunk of bread, working out whether it was real or fake. We decided that truth had something to do with “everything matching”, no matter how much information we gathered about it. So our internal idea about something must match the external reality.

Insufficient or imperfect information?

Things get more complicated, though, if the information we can gather about something is insufficient or imperfect:

- Maybe that ‘something’ is too big for us to examine from every angle.

- Maybe it’s inaccessible to us.

- Maybe it’s always changing, so we’re only ever examining it under specific conditions.

- Maybe it’s too vague or ephemeral.

That leaves plenty of room for ambiguity. Because instead of one internal idea matching external reality, there are now potentially multiple matches.

Conflicting opinions?

The situation gets even more complicated once someone else gets involved in our hunt for truth. They face the same challenge we do, with the added complication that their multiple matches might not agree with our own multiple matches!

How, then, can we ever know the truth if there are multiple matches?

In this article we’re going to untangle the relationship between truth, knowledge and belief. We’ll even see that it’s possible for us to possess the truth without actually knowing it, how easy it is for us to mistake belief for knowledge, and why our pre-existing beliefs about something often get in the way of knowing the truth, both at an individual level and at a societal level.

Possessing the truth without knowing it?

There are many things in life we can never fully know. Maybe they’re too complicated, too big, too inaccessible, too changeable. Knowing the future is the perfect example of this, but it applies to any subject matter that is beyond our capacity to know as finite human beings, limited as we are in space and time.

Yet surprisingly, it’s still possible for us to ‘possess the truth’ about something without necessarily knowing everything there is to know about it:

- We could possess the truth by accident: a lucky guess, for example.

- We could come into possession of something without having the knowledge to understand its significance, such as discovering an abandoned laptop containing details of some classified but shady dealings.

- We may have been told something that was true by someone else, even though we didn’t examine the information directly ourselves. Weirder still, the person who told us ‘the truth’ might not even have known it was true; they could even have believed it was untrue!

Clearly possessing the truth is not (necessarily) the same as knowing the truth. Which suggests that:

Truth remains independent of knowledge, but knowledge is always dependent on truth.

The difference between ‘possessing’ and ‘knowing‘

To illustrate the difference between possessing the truth and knowing the truth, imagine correctly guessing next month’s winning lottery numbers. There is no way you could know your guess was correct because the winning numbers haven’t been announced yet, nor have the numbers even been selected.

So your possession of the truth here is not equivalent to knowing the truth, unless:

- You are somehow involved in ‘fixing’ those results

- You’ve received information from someone involved in fixing the results

- You have some way of accurately perceiving (rather than merely predicting) future events

Even so, you may convince yourself you really do know those winning number. You may even convince others that you know, especially if your confidence is unshakeable. But you do not know, for the simple reason that the winning numbers have not yet been drawn and they have not yet been announced. Therefore there is nothing external to match your internal idea to.

Even if they had been drawn and announced, until you personally have heard or seen the official announcement, you do not know.

Because to know, everything has to match:

- Your own internal idea about the winning lottery numbers

- The external something, i.e. the drawing and announcement of those numbers

- Reliable sensory confirmation that matches your internal idea to the external something

Until that match is complete, what you have is belief, not knowledge – no matter what your hindsight might tell you: “See! I told you I knew. I just knew!!”

Temporary placeholders for knowledge

What we believe to be true is often mistaken for ‘knowing’, especially if we’re certain. That’s because beliefs are temporary placeholders for knowledge we do not (yet) possess, so they behave exactly like knowledge.

Beliefs allow us to take action whilst uncertainty remains. Sometimes, if we act as if we know, we can even create the right external conditions for our belief to become reality, such as with a self-fulfilling prophecy. But that’s for another discussion.

In summary, whilst gaps remain in what we know about something, the best we can honestly say is that we believe something is true to the best of our current knowledge. But if we want to know the truth, we’re going to have to gather all the information there is to know about something, to see if all that new information matches our belief too. If it does match, it’s more likely to be true, assuming we’ve not missed something crucial that would “turn everything on its head”.

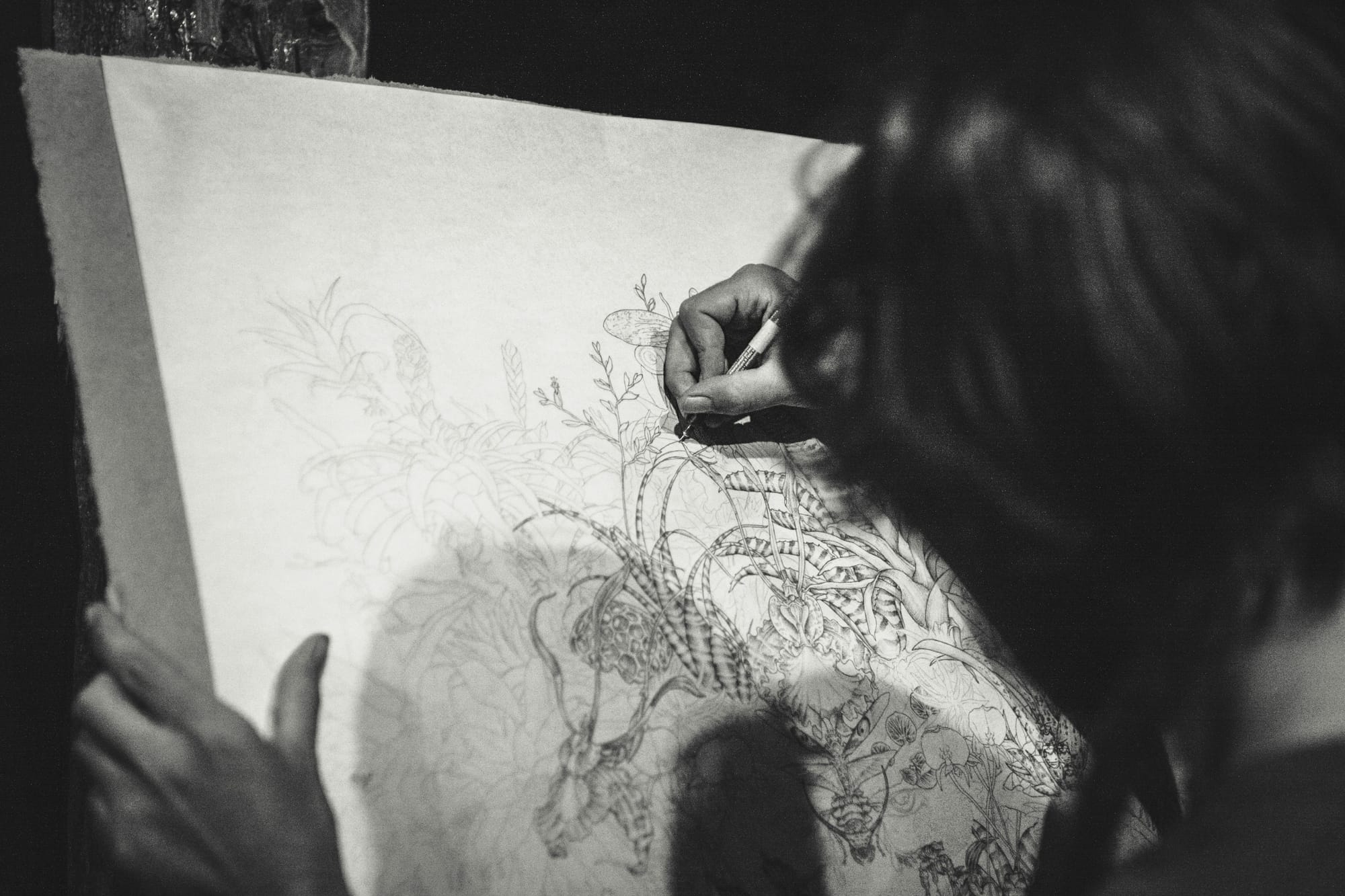

A belief is a like an artist sketching something out in pencil first before using a more permanent medium like ink or paint.

Turning belief into knowledge

If a belief is a temporary placeholder for knowledge, doesn’t that mean we can turn our belief into knowledge by gathering the missing information, then?

In theory, yes.

But even if we try to gather the missing information, there’s a tremendous risk we’ll deliberately seek out things most likely to match our pre-existing beliefs whilst conveniently ignoring anything and everything that might not match.

Collective Cherry-Picking

Such widespread cherry-picking doesn't just apply to us as individuals.

Institutionalised belief systems will often differentiate between ‘orthodoxy’ and ‘heresy’, even going so far as to penalise adherents for asking questions, reading the wrong material, or saying the wrong things.

This zealousness for what the individual or collective believes to be true frequently sabotages any chance they might have of actually knowing the truth… especially if their identity or raison d’être depends on that belief. (Imagine the consequences if such zealousness was combined with power…)

But why is it that so many of us, either at the individual or collective level, fall into this trap of cherry-picking?

That’s what we’ll look at in the next article.

Conclusion

Knowing the truth about something is fairly straightforward if the subject is self-contained and unchanging, readily accessible to us and understandable, and if we are able to examine it from every perspective to rule out alternative matches for the information available. But once something exceeds our personal capacity to fully examine it, we’re going to have multiple possible matches for that information. That’s when we must begin sketching in the possibilities with our beliefs—those temporary placeholders we use for the information we’re currently missing.

Those beliefs may be absolutely 100% true (e.g. there is/isn’t life after death for us), but that’s not the same as us knowing the truth—because although we might possess the truth, we haven’t yet matched our internal idea to the external reality through our senses. It might not even be possible for us to do so, especially if the something we’re trying to know is too complex, too dynamic, too ephemeral, or beyond our finite capabilities to perceive or comprehend it.

This means that even if we do happen to possess the truth (e.g. by accident), we still do not know the truth. So we must continue to incrementally convert our beliefs into knowledge through gathering information and systematically excluding all other possibilities. The problem comes when we forget the second part of this conversion process by ignoring or dismissing the alternatives. Instead we cherry-pick the information that matches what we’ve already decided must be the truth, even though it’s impossible for us to know for certain. As a result, instead of our beliefs leading us towards truth (through progressive knowing), they keep us from it.

Worse, if we have power over the decisions, opportunities and relationships of others, we may even find ourselves keeping others from knowing the truth too.

Seeking and finding truth therefore requires us to avoid cherry-picking. The question is, why do we want to cherry-pick in the first place? And what’s the antidote? That’s the topic of our next article.