Outsourcing Our Personal Quest for Truth

When things are too complex or we can't invest time and effort getting to the truth, do we outsource our quest to others, assuming they know best?

In Bubbles of Certainty we saw how all of us carve out little spaces of predictability and certainty from the chaos of life by wrapping ourselves in self-contained knowledge where all the evidence we possess ‘makes sense’. We then divide the world up into those who are with us (or like us), and those who are against us (or unlike us). Those who are with us see the world the same way we do, whilst those who are against us see the world differently.

The resulting certainty we feel when ‘all the pieces fit’ and we surround ourselves with those who think the same way we do leads to the conviction that we have discovered “the truth”. We fool ourselves into believing we have no need to look outside our own Bubbles of Certainty, nor waste time even listening to the opinion of anyone with a different perspective. We’re right, so they must be wrong.

Most of the time, this strategy works—at least in terms of maintaining our personal Bubbles of Certainty, though it frequently creates problems for wider society. But what happens when we encounter a new situation or information that we don’t (yet) have an answer for? And what about those things that are too complex for us, or require further investigation than we have the time, skill, resources or motivation to pursue?

That’s normally when we outsource our personal quest for truth to others.

Two Strategies for Finding Truth

When we encounter new information or a situation for which our current thinking has no answer, we have two choices:

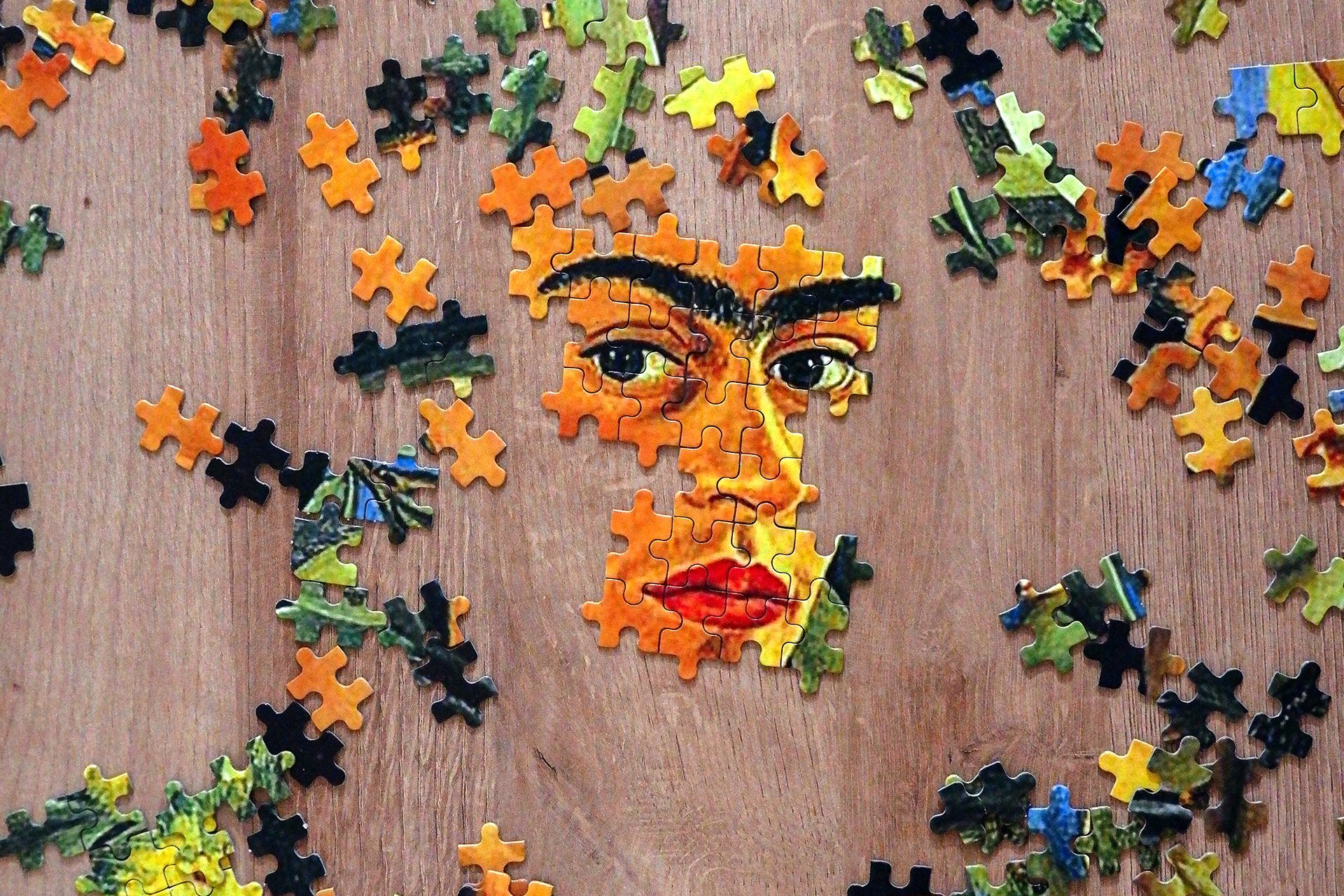

- EITHER: We can find all the pieces of the puzzle ourselves (or in collaboration with others) and try to work out how all those pieces fit together.

- OR: We can find someone we believe has completed the puzzle already.

It’s all about priorities

It’s obvious that the first strategy—working everything out for ourselves—requires the most time and effort. That’s time and effort which must be taken away from other things that may be more important to us, such as family, work, hobbies, relaxation etc. Our motivation to work on the puzzle must therefore be greater than our motivation for any competing priority

The choice we ultimately make can tell us something about which we value more, or perhaps the expectations that others have of us.

Something missing?

Trying to piece together the puzzle ourselves can also be immensely frustrating, especially if we don’t have any idea of what the finished puzzle is even supposed to look like, or if we’re not sure which pieces fit where.

It can be even more frustrating if we’re not sure we even have all the pieces. Perhaps some of those pieces are now lost forever, like that elusive jigsaw puzzle piece missing from the box we picked up at a charity shop or thrift store. Imagine what mysteries we might unravel if the Great Library of Alexandria had not been destroyed, or if we could speak directly to those who designed and built Stonehenge, or if we had the means to decipher the Voynitch Manuscript (or determine once and for all that it was indecipherable).

Everything fits, but…

If a puzzle is especially complex—which can be as true of scientific mysteries as it can be of political and corporate intrigue—it may even look as if everything fits together, yet still be wrong. But how would we know? Unlike a jigsaw puzzle, which helpfully provides us with an example of the finished product (‘the truth’), real life mysteries are frequently far less accommodating. There’s no checking our answers at the back of the book. We might all come to very different answers (such as questions of morality or interpretation of meaning) and have no way of deciding between them.

So despite tremendous personal investment in time and effort, we may still find ourselves with crucial pieces of the puzzle missing. We are no more certain, yet have wasted precious resources in the process. Furthermore, by venturing into the unresolvable, we may find our Bubble of Certainty threatened, perhaps irreversibly ruptured. We are left feeling incomplete, unsatisfied, even uncomfortable.

Take this burden from me

Wouldn’t it be easier if we could simply have someone do all the hard work for us? Someone whom we could trust to neatly package everything up for us, presenting us with a finished product in which all the pieces have been conveniently fit together and everything just makes sense. Even better, if they could wrap it up for us with a catchy slogan or attention-grabbing headline. Any uncertainties that might remain, we could safely leave in their doubtlessly capable hands; they wouldn’t need to bother us with such trivialities such as nuance or contextualisation. Their confidence would give us confidence. Their certainty would be our certainty.

This is where the second strategy comes in:

Outsourcing our certainty…

- To the Experts – we assume that because they have specialist knowledge, training and skills that we do not possess, they must have answers that are unavailable, incomprehensible and inaccessible to the rest of us.

Examples: Scientists, Academics, Doctors, Engineers, Intelligence Agencies, Pundits, (Non-fiction) Authors etc. - To the Authorities – we assume that because they have power, they must have somehow earned it—through character, competence and by winning the respect of others. We assume this makes them uniquely capable of better judgement and insight than those without power, such as ourselves. (Besides, they often have the law on their side so it’s very hard to disagree with them, at least in practical terms.)

Examples: Rulers, Government (including Politicians and Councils), Law Enforcement, the Judiciary, Regulators, Admissions Boards etc. - To the Enlightened – we assume they have access to privileged knowledge because of their special relationship with someone or something that possesses the answers.

Examples: Priests, Gurus, Elders, Senior Statesmen or Stateswomen, Ancient Texts (and Tradition), Artificial Intelligence etc. - To the Successful – we assume successful people possess qualities that make them uniquely capable of doing things that the rest of us can’t, including resolving uncertainty or paying for those who can resolve it for them.

Examples: Billionaires/Philanthropists, World Leaders, Founders of Companies, Heads of Organisations (especially if they’re global), Film Directors, the Famous etc. - To the Media – we assume that the Media investigate every topic thoroughly and objectively, that they are impartial, that have no vested interests, that they never allow personal bias, political leanings or commercial interests to affect what they choose to report or not report, and that they follow a strict code of ethics which prevents them from deception, exaggeration, misrepresentation or cherry-picking.

Examples: Television, Newspapers, Social Media Platforms, Journalists, Presenters, Interviewers, Documentary Makers etc. - To the Crowd (a.k.a. ‘the Consensus’) – we assume that if a large group of people have all come to the same conclusion, there is a good chance that the conclusion they have reached (we assume: independently) is likely to be correct. There’s “wisdom in crowds” and “safety in numbers”, but the lone wolf and outcast you have be wary of.

Examples: Opinion Polls, Collaborative Reports, Joint Statements, Social Media Likes/Shares, Protests etc. - To the Confident – because confident people display less uncertainty than we feel, we assume they must have been able to take the same information and missing pieces we possess and somehow satisfactorily solve the puzzle. Why else would they appear so confident?

Examples: Leaders, Press Secretaries, PR Companies, Propagandists, Visionaries, etc. - To our Peers – we assume that people who are most like us are also likely to think and feel the same way we do. We therefore assume that if they propose an answer that seems to ‘makes sense’, that answer is likely to be correct because it is the one we too would probbably have reached, had we invested our own time and effort.

Examples: Our Own Generation (especially Friends), Shared Political Leaning, Same Religion, Same Ethnicity, Role Models, Social Media Influencers, Podcasters, Soap Characters etc.

Trust me. I’m a successful authority who represents the confident consensus of peer-reviewed experts.

In many cases, all such outsourcings may indeed be more capable of resolving uncertainty about an issue than we can personally.

But there’s another advantage. If they turn out to be wrong, we’re surely not to blame for trusting them, are we? Didn’t they betray our trust? Which is why outsourcing our certainty turns out to be a wonderful way to abrogate personal responsibility…

…especially if someone ends up getting hurt in the process.

- “I was only following orders.”

- “The regulator said it was safe.”

- “The Media/Politicians have a lot to answer for.”

- “It was perfectly normal in those days.”

- “He seemed to know what he was doing. I had no reason not to trust him.”

- “She was a friend. I thought I knew her.”

Because the downside of outsourcing our certainty is that we have to trust that they have completed the puzzle (when we haven’t), that they have completed it correctly, and that they share the same values we hold.

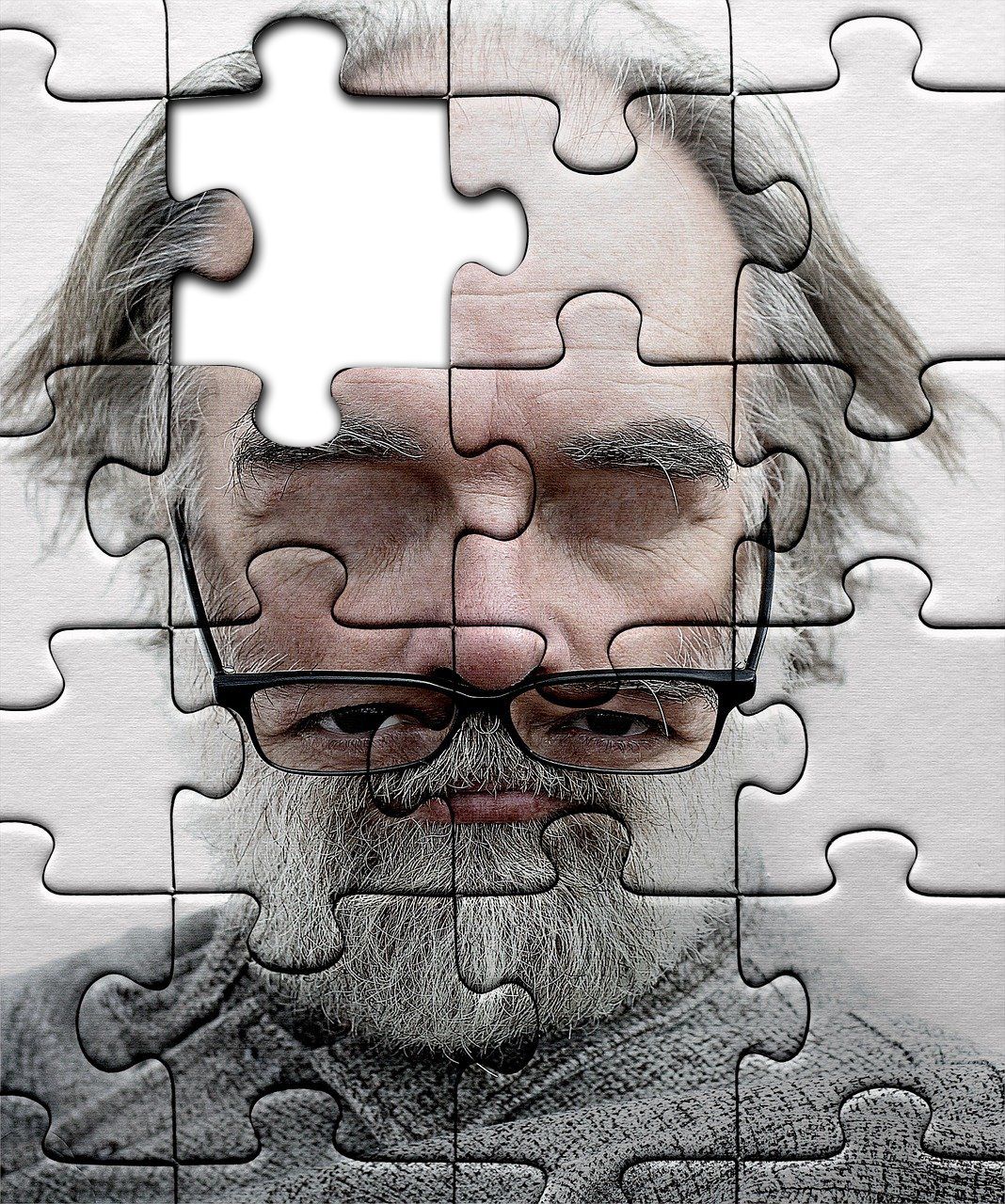

But when we outsource to others, we only ever see the finished product. The ‘truth’ we see is carefully packaged, neatly presented to us with no loose ends. We forget that they too will have had the same messy frustrations finding and fitting all the pieces together. That they too are only human.

Because to us, it all looks ‘perfect’.

Everything fits. There’s nothing out of place.

Therefore it must be true.

Or so we assume.

Conclusions

No human being can every fully understand reality in its entirety. That means that all of us will eventually come across things we have no answer for, especially when dealing with increased complexity. All of us have to outsource our certainty to others on occasion, whether we’re listening to an expert explain something, in a meeting with a healthcare profession, dealing with the authorities, or simply reading a textbook or news report. Not only does outsourcing our certainty allow us to invest valuable time and effort in more rewarding pursuits and priorities, but it reduces our feelings of unease when our Bubbles of Certainty are threatened.

The problem comes when we forget that the people and institutions that we outsource our uncertainty to are also human. Just like us, they too are constrained by the same human finitude and biases we all share—no matter how confident and assured they may appear to be.

None of us can know all the answers. We can’t even come close in a single lifetime, so it is only natural for us to outsource our certainty to one another. This is a good thing, because it creates interdependence and relationships.

But never forget that outsourcing is a belief. It is a belief that those we choose to outsource our certainty to are correct and that their values align with our own. We cannot know this for sure—not unless we can compare what they are telling us to Truth itself. But unlike a jigsaw puzzle, we don’t have the benefit of a physical box that shows us all unambiguously what the completed image (“Truth”) is supposed to look like.

Which brings us onto the subject of our next article: What is Truth?

Key points

- Practice identifying when you are outsourcing your own certainty to others and learn to recognise what it is you are outsourcing to, e.g. Experts, Authority, Peers etc.

- Regard any outsourcing you do as you would any other belief. Beliefs are temporary placeholders that must be continuously tested to see whether they can stand up to attempts to bring them down. Truth will stand not matter what gets thrown at it.

- Always be ready to update or replace your current beliefs when something closer to the Truth comes your way.