What is Power? Part 4: Absolute Power

Why is power addictive, and why do people with power often become indifferent to the needs of others? Can someone en route to absolute power be stopped?

In Part 3 we established that the minimum level of power was zero, or ‘powerlessness’.

We also concluded that once something moves beyond being powerlessness, ‘power’ and ‘the potential to cause change’ are equivalent, so that if we wanted to quantify the amount of power something possesses, we would simply need to ask how much change could it cause.

Now that we have our minimum, we next need our maximum, commonly referred to as absolute power. We’ll start our investigation with the principle that to measure power, we need to quantify the potential for causing change. On this basis, then, absolute power requires absolute change. The common use of the word ‘absolute’ implies complete or total, and that’s the meaning we’ll use here.

Absolute change

We’re looking for a simple example where we can observe complete or total change, to see if we can identify some key principles we can then generalise to more complex examples.

When something that is becomes something that is not, we can conclude that there has been absolute change. The same is true when ‘is not’ becomes ‘is’.

On this basis, the simplest (and easiest to understand) example of absolute change is an ‘either/or’ binary in which being one thing prevents it being the other. There is no position in between the two states. It is either one thing or the other. So something is either up or down, front or back, yes o or r no, Head or Tails. Thus, being one of the two paired states defines the other possible state.

It’s rather like a conventional light switch (without a dimmer):

- Flick the switch ‘on’—the light comes on.

- Flick the switch ‘off’—the light goes off.

So the maximum change here is a complete inversion (and eradication) of the light’s previous state. The state has changed absolutely.

In the eye of the beholder

But flicking a light switch on or off hardly feels like possessing absolute power, does it?

Maybe that’s because we’re not the light. Remember, we’re the ones causing the change. We know that we have many more actions we can (and cannot) perform besides the simple act of flicking a light switch on or off.

Conversely, if we’re the light itself, our entire existence has been altered by someone other than ourselves flicking that switch. The light has gone from not existing to existing, and back again. If the light were conscious, and if the light had no capacity change itself, then it is us who are solely responsible for its ‘being’. As far as that light is concerned, we are indeed all-powerful.

Putting power in perspective

From this we can make the following observations:

- Subject vs Object

How we quantify power depends on whether we consider power from the perspective of the thing causing the change (the Subject) or the thing on the receiving end of the change (the Object). - Total inversion

When the Object has two possible ‘either/or’ states, absolute change is an inversion of one state to become the other.

So from the perspective of the Object, the change is absolute, which means that the power too is absolute. But from the perspective of the Subject, that same use of power may be a mere fraction of their total power.

When more becomes less

To illustrate the significance of which perspective we’re considering power from—the Subject’s or the Object’s—let’s expand the number of light switches we’re working with.

If we have ten light switches that we can change, flicking one switch represents just 1/10th of the power we have over all those lights. We could increase the number of light switches to 1,000 and now one switch represents a mere 1/1,000th of our power over the lights. Every time we exercise our power over a single light, it is now but a fraction of our total power.

Yet from the perspective of each light switch, our power has not been diluted by the increase in available light switches.

From each light’s perspective, we still have absolute power over every single one of them. For them, nothing has changed. Their existence is still in our hands.

What has changed is only from the perspective of the person flicking the switch. Change at the Subject’s level has become increasingly trivial as the extent of their power increases.

Power and satisfaction

As our power increases (more lights we can change), exercising power over a single light switch no longer offers us the same sense of absoluteness (or completeness) that we got when there was only one light switch in total.

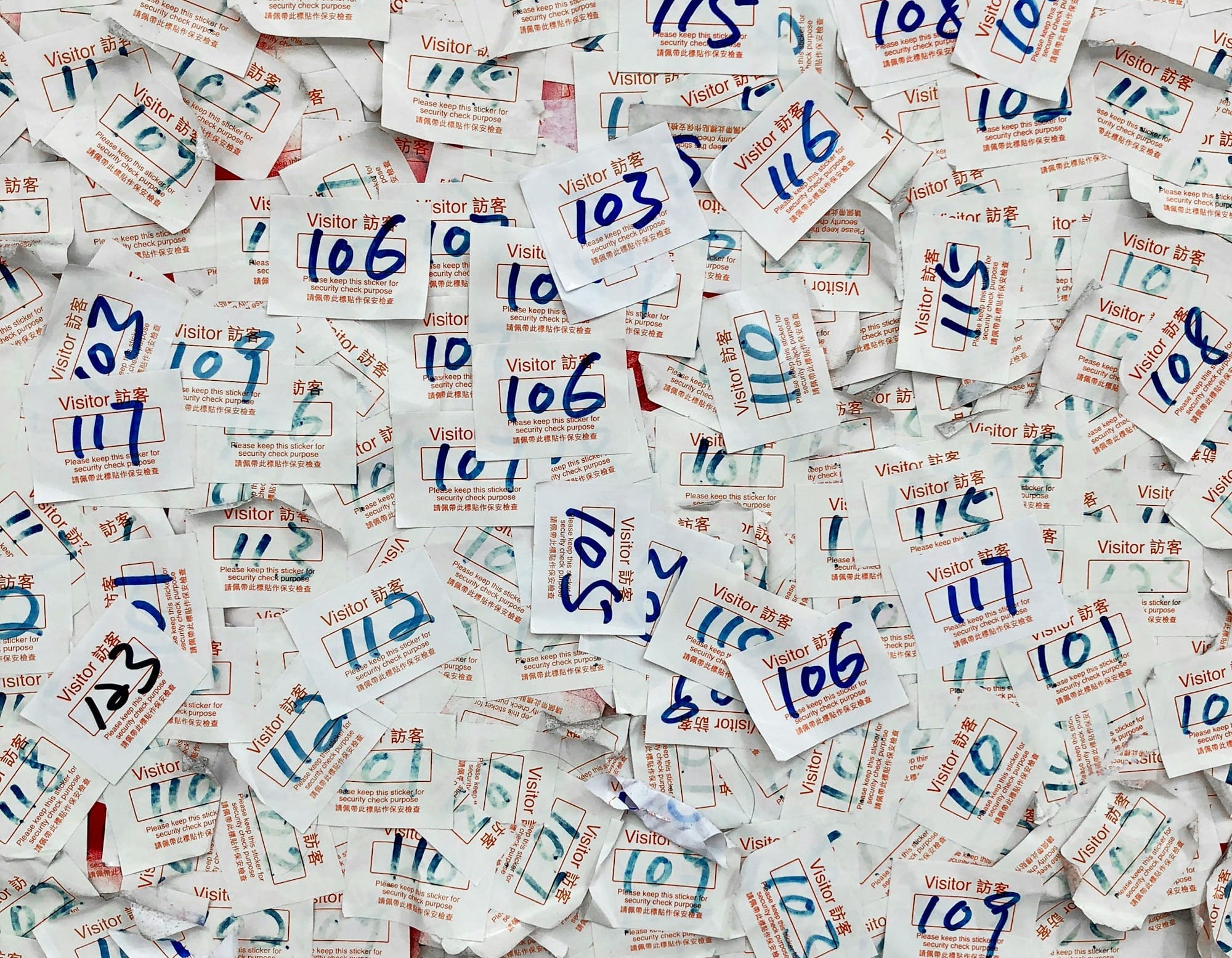

To regain that sense of absoluteness, we would have to change all the switches. We no longer consider them at the individual level; we see them en masse, as a homogenous group. They become statistics or numbers to us, losing their individuality and intrinsic value.

Dilution, Disconnection, Detachment

Thus we see that:

- As the Subject’s potential to cause change increases, so too does the disconnect between the Subject’s own perception of their power and the Object’s experience of that power.

- Whilst the Object’s experience of the power remains absolute (it’s their entire existence), the Subject’s own feeling of it becomes diluted.

Together this makes it increasingly difficult for the Subject to recognise or appreciate any effect their power might have on the Object. They become detached, even hardened. Thus, if those changes cause suffering to the Object, chances are the Subject would become increasingly indifferent as their power increases.

Can’t get no satisfaction?

This increasing disconnect sets up a fascinating possibility: that as the Subject’s power increases, the Subject may feel as if their power is actually diminishing!

Not only this, but their feelings of incompleteness may increase too. Thus, increasing and exercising power produces a hole that needs filling, but it’s one that can never be satisfied.

Isn’t it plausible that the Subject would subsequently seek to increase their power in order to recover that lost sense of absoluteness they once felt when they first exercised power? Would they not seek to replicate that first and only time they felt a perfect match between exercising power and the satisfaction of causing absolute change?

Vicious circles of power accumulation

As we saw when we increased the number of light switches, acquiring more power ironically increases the Subject’s own sense of diminishing power.

So by trying to recover that lost sense of absoluteness, they seek more power, which only dilutes the sense of absoluteness further. They find themselves trapped in a never-ending cycle of seeking power to satiate an ever-expanding hole.

Thus we have all the makings of a vicious circle of power accumulation.

Personality and power?

Given this relationship between power and the sense of absoluteness, could it be that certain personality traits will be more vulnerable to such vicious circles?

- Those with a perfectionist nature who feel uncomfortable with incompleteness.

- Those with a lower capacity to see their own actions from their Object’s perspective.

If this turns out to be so, perhaps an antidote for such vicious circles would be to instil potential possessors of power with a tolerance for the incomplete and imperfect, coupled with empathy.

Beyond reach?

This assumes, of course, that it is even possible to influence such candidates. Irregardless of personality trait, whenever a Subject gains more power, their amenability to external influence diminishes accordingly. Why? Because the more a Subject can do for themselves, and the more that others around them say “yes”, the less need they feel for the input or guidance of others. Once again, we see that power has a tendency to breed indifference.

And what if the Subject has always known power? What if they were born expecting others to automatically say yes? In such cases, it’s not easy to see where the opportunity to instil tolerance and empathy might come from.

Extending power

If we are the Subject flicking the light switch, we could keep extending our power indefinitely by bringing more and more light switches under our control. Increasing our power in this manner doesn’t even require imagination—we could simply do the same thing we’ve already been doing, but to more things. All that’s required is for us to:

- Become aware of those additional switches (knowledge/information)

- Find a way to bring them within our capacity to change them (access/reach)

“Knowledge is power”

The need to become aware of other things we could change implies there must be a relationship between knowledge and power. This makes sense. If something is outside of our knowledge, how do we know if we can change it and how we can change it?

Is this why we’re told that “knowledge is power”?

But to suggest knowledge and power are synonymous would be a gross over-simplification. So for this purposes of this article, let’s just say that knowledge is a prerequisite for intentional change. In other words, knowledge tells us if we can change something, and how. Whether or not we want to change it will depend on our intention. We’ll look at this more in a future article on Power and Purpose.

Limitless power?

As long as we don’t run out of light switches, there is no maximum to how much power we could gain. Our potential accumulation is only constrained by our own limitations: at some point we would no longer have the time nor energy to keep switching light switches on/off personally. Either that, or some light switch would escape our notice or reach.

Maximum power is limited by our own capacity, just as the maximum speed of a vehicle is limited by the size of its engine.

Recruiting others to overcome our limitations

But what if we could recruit others to act on our behalf? What if we could utilise others to overcome our own temporal-spatial limitations? Providing they acted exactly as we would, would they not then become an extension of ourselves? Such an extension would effectively increase our own capacity and, consequently, our own maximum power.

How the Subject might recruit others to act on their behalf is a topic we’ll reserve for a separate article. And yes, coercion (the exercise of power over another) and shared beliefs/goals both have roles to play here.

Six limits on ever-increasing power

So far we’ve established that power can be increased, presumably until we reach an eventual point of absolute power. But if absolute power is to even become a possibility, the Subject would need to avoid anything that could limit their power accumulation.

Let’s summarise the limits we’ve encountered above:

- The Subject reaches their maximum capacity to cause change.

- The Subject runs out of energy.

- The Subject runs out of time.

- The Subject can’t find or recruit others to act on their behalf

- Something with opposing power prevents the Subject causing change.

- The Subject runs out of things they can change.

These 6, then, represent natural limits on ever-expanding power:

1️⃣ Capacity

2️⃣ Energy

3️⃣ Time

4️⃣ Compliance

5️⃣ Opposition

6️⃣ Availability of things that can be changed

The last one on the list, availability, may be due to a limit in the Subject’s knowledge or their access to things that can be changed. But it might also represent the point at which there’s nothing else left that can be changed. If it’s the latter, then it suggests absolute power has been achieved.

Recognising the signs of power accumulation

If we happen to notice someone or something attempting to overcome any of these 6 limits, it’s a sure sign they're attempting to increase their power.

By learning to recognise these signs, not only will we improve our vigilance against those wishing to exercise power, potentially over us, but it will also highlight where the Subject believes themselves to be currently vulnerable. When we begin discussing Power and Resistance in a future article, this is where a resister would want to target.

Criteria for possessing absolute power

Given the 6 limits to ever-increasing power described above, it stands to reason that to achieve absolute power the Subject must meet the following criteria in order to secure absolute power.

- Complete access to the System.

- Complete knowledge of the System.

- They must have the potential to change everything within the System. This means that their own capacity to cause change needs to match or exceed the capacity of the System to be changed.

- Sufficient energy and time to implement all potential change within the System.

- No equal, opposing or greater power, either within the System itself or externally.

But what do we mean here by “the System”?

Defining the System

In the case of the light switches, we might define the System as:

- Example 1: “All light switches currently in existence.”

- Example 2: “All light switches in a specific house with a specific sole occupant.”

- Example 3: “This specific light switch.”

In the first example, it would be hard to imagine a single human being possessing absolute power over every light switch in the entire universe, unless all those light were somehow networked. But it’s not so difficult to imagine a human being having absolute power over the System as defined in Example 2 and 3.

When it comes to absolute power, how we define the system is therefore essential.

Absolute power is always contextualised by a definable system.

Explaining differing perceptions of power

This principle—that absolute power is always relative to the System—is important for us to grasp.

Notice how neatly the principle explains that perceptual difference we noted earlier, how the Subject with power rarely perceives themselves to have absolute power, even though the Object on the receiving end of that power believes they do.

Let’s unpack this a little to see how the principle works:

- For the Subject, what they define as the System is everything they want to be able to change. If some of that System is beyond their power, they will not perceive themselves to have absolute power.

- For the Object, the System is contextualised as just themselves. For them, everything else falls outside the System. Why? Because it’s not them. They’re not interested in any of the other things that the Subject might be concerned about.

- If the Object’s existence depends entirely on the Subject—as in the example with the light switch—then, as far as the Object is concerned, the Subject possesses absolute power, irrespective of what else the Subject can and cannot do.

The System limits the Subject’s power

This relationship between the Subject and the System leads to a surprising discovery. It means that:

The Subject’s power is inseparable from the System that it seeks to be able to change.

For the Subject’s power is always defined (and limited) by the changes that can be made to that system.

To understand this, consider the following examples:

- A king is not a king without a kingdom.

- A lion-tamer is not a lion-tamer without a lion.

- A judge is not a judge without someone to judge.

For a subject to possess power, it has to have something that it can change. If a system cannot be changed, what power does the Subject possess over that system? None whatsoever. Or zero, which—as we discovered in Part 3—is the very definition of powerlessness. But clearly absolute power and powerlessness cannot be equivalent to one another.

So the Subject needs the System for their own power to exist. More than this, they need a system that can be changed.

Absolute power depends on the System

So we discover something new about the limitations on power. It is not just the capacity of the Subject to cause change that limits absolute power. It is also the capacity of the System to be changed.

It therefore follows that the Subject’s capacity to cause change and the System’s own capacity to be changed must align with one another.

Providing change is possible, absolute power is reached when the Subject’s capacity to cause change matches or exceeds the System’s maximal capacity to be changed.

Irreversible change and loss of power

But what if, through the Subject causing change, the System becomes incapable of being changed any further?

Then the Subject loses their power!

To understand this, consider again our lights. We can turn those lights off temporarily by using the light switch, but we could also turn them off permanently by smashing the bulbs.

In both cases, we have demonstrated power over the lights. But there’s an important difference. In the first example, we retain our power because we can change them again, but in the second example we lose our power because the change we have implemented is irreversible.

Absolute power endures only as long as the System endures and remains changeable.

This presents the Subject with a problem: if they derive satisfaction and purpose from causing change, then once an irreversible change has taken place, won’t they have destroyed their source of satisfaction, purpose, even identity? For what is a king without a kingdom?

If, on the other hand, an irreversible change makes further change to the system possible, their power over the System is retained, and may even be increased.

Summary

We have now defined our maximum level of power: absolute power. We discovered that absolute power is inseparable from a system, and this system must be definable, it must exist, and it must be changeable.

To achieve absolute power over a system, the Subject must have sufficient capacity, knowledge, energy and time to be able to change that system completely, without anything resisting the changes it wants to make. If the Subject wishes to retain their power, any change to the system must either be reversible or make further change possible.

As power increases, the Subject who possesses the power becomes increasingly disconnected from the impact their changes have at the individual level. Whilst an individual’s entire existence may depend on the Subject’s power, that individual may be just one of many for the Subject, an insignificant fraction of what they can or cannot change, helping to explain the indifference often associated with power.

And as we will see in our next article, Power and Relationships, this disconnect between the Subject and the Object that comes with increasing power undergirds much of what society has historically considered unjust or oppressive. It also help us unravel the frequently rocky relationship between “the people” and those “in power”.